Farah Nabulsi | Artistic resilience

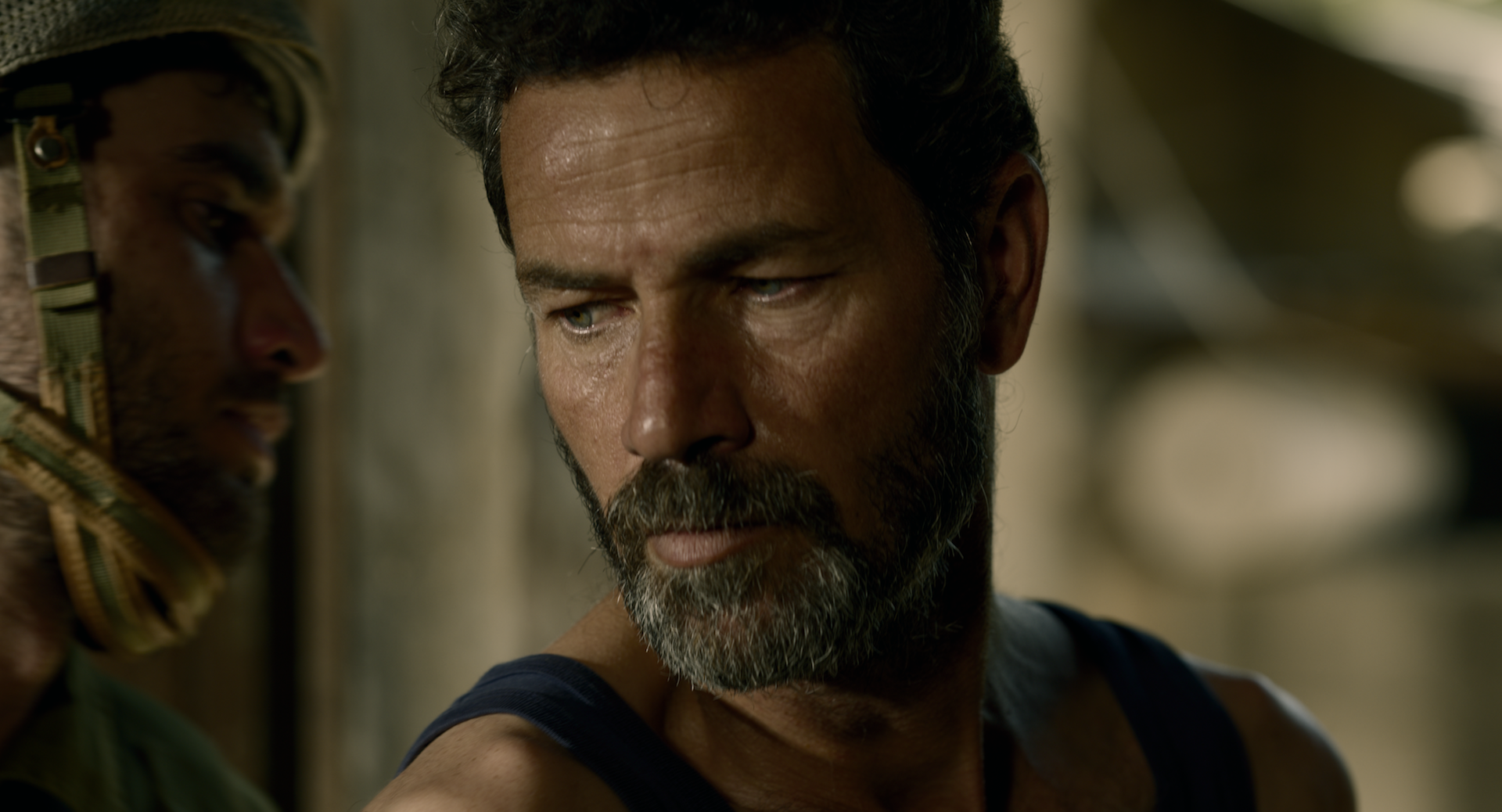

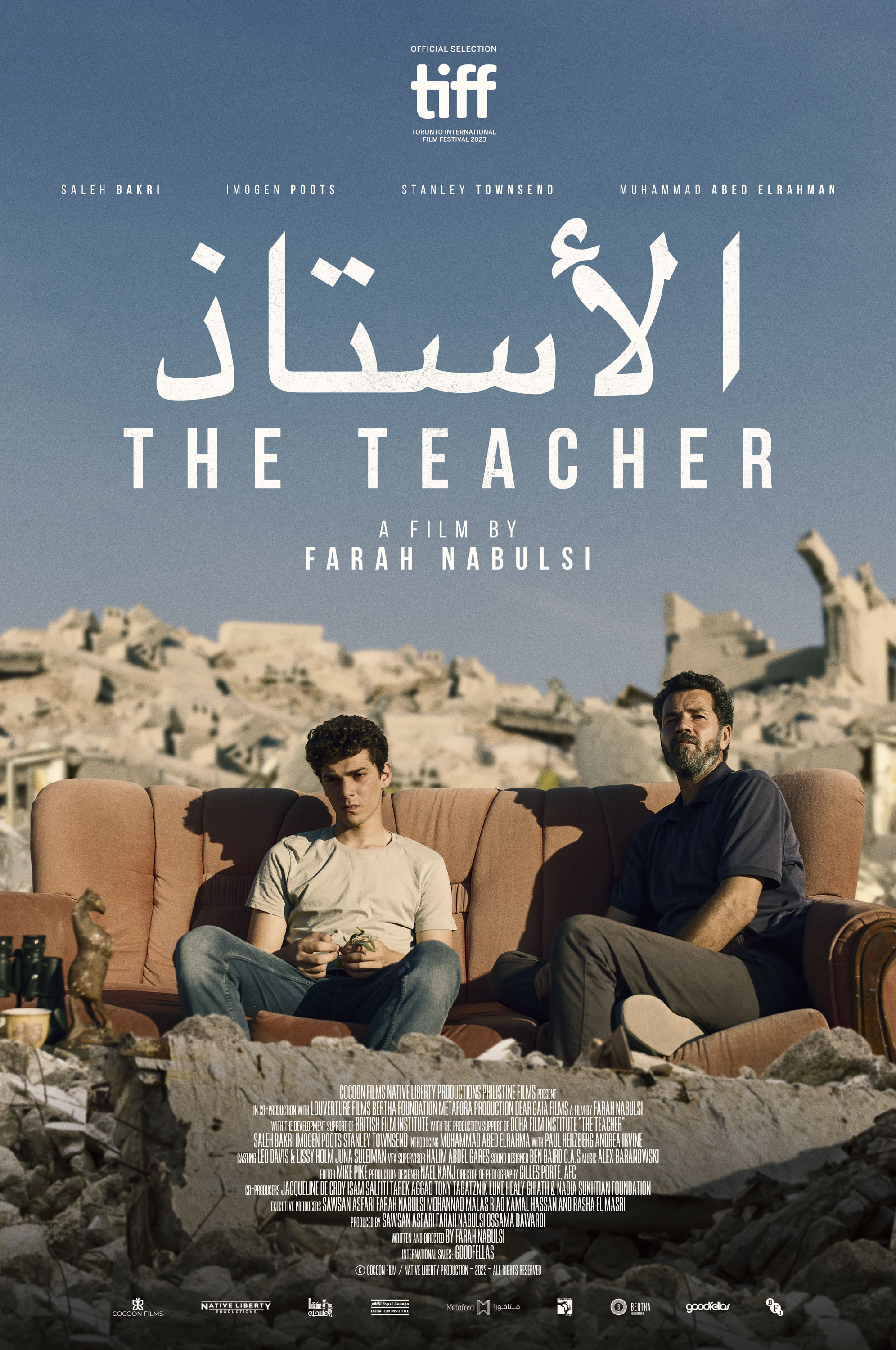

She chose the cinema to tell it. British-Palestinian filmmaker, Farah Nabulsi goes all out, delving into the depths of her country and its history, unabashedly and with artistic sincerity and naturalness. Occupation, resistance, love, dignity, resilience... This life that is theirs and which she distills in her latest work, The Teacher, sheds light on the tragedy and hardships of life in the occupied West Bank. A story of loss and love, juxtaposed with an intertwined quest for freedom. Awarded at the BAFTA and nominated for an Oscar for her first short film The Present, she is the voice of a people committed to preserving their identity, dignity, and freedom. To be heard and to exist, she takes her camera, interrogates war, explores anger and grief. Seven months after the start of the war waged by Israel following the Hamas attack, it is at the FIFDH in Geneva for the European launch of her film that we meet her. In a world that is anything but gentle, let’s revisit a revitalising conversation, where the filmmaker’s pacifist commitment remains more vibrant than ever.

.jpg)

Lisa Cherifi: You studied finance and worked in that field for much of your life. Why did you decide to leave it all behind to pursue filmmaking?

Farah Nabulsi: To be honest, I didn’t really have a choice; I felt compelled to tell what I had witnessed and the colossal injustice unfolding before my eyes. You see, I was born, raised, and educated in the UK. As a child, my parents and I visited Palestine several times, but after the first intifada, nothing for 25 years. About ten years ago, I went back for the first time as an adult, rediscovering my heritage, culture, my ancestors’ home, my blood... It completely changed me! Then, It took me a few years of back and forth to absorb what was happening before my eyes. I spent a lot of time on the ground with the people, who experienced all the things I depict in my films. So, I simply couldn’t go back to my privileged life, as if I had never known or understood what was happening. So, I had to make a choice, and I did.

________________________

“I felt compelled to tell what I had witnessed

and the colossal injustice unfolding

before my eyes.”

________________________

LC: The Teacher was filmed several months before the start of the war. What was your initial intention in making it?

FN: One of the main reasons why this kind of injustice is allowed to persist for so long and on such a scale is that people aren’t emotionally engaged enough with the Palestinians. And I think that’s probably the case for all injustices that are allowed to perpetuate. Not enough people are feeling enough and therefore not enough are taking concrete action to bring that oppression to an end. So, as a filmmaker, my intentions are to take the audience on an emotional journey. The main way we, as a society, can bring people to act for a cause or alongside those facing injustice is through cinema, through art, really. Because art speaks to the heart and not the mind. Particularly with The Teacher, I wanted to get the audience to reflect on the experiences of the characters and the choices and decisions they were forced to make in a very cold reality.

LC: How do you perceive the role of art in the discourse around war and in the emancipation of the Palestinian people?

FN: Art is called soft power for a good reason. It has the power to basically tear down stereotypes, overcome misconceptions and misperceptions and provide a voice to people whose voices have been silenced or ignored. For me, the most powerful form of art and communication the world has ever known is cinema. So, in doing so, in telling stories through cinema, through art, you’re taking back your narrative from the storytelling and you’re no longer allowing your narrative to be hijacked. And for Palestinians, their narrative has been hijacked for decades so it’s a way of reminding people, our way of culture, the kind of people we are, and that Palestinians love, live, breathe, laugh, like anyone.

_________________________________

"For me, cinema is the most powerful

form of art and communication the

world has ever known."

_____________________

.jpg)

LC: The film was entirely shot in the occupied West Bank in a very complex political context and environment. What were the challenges on the ground and how did you manage the logistics as a woman, Palestinian, and director?

FN: Making an independent film, no matter where you are in the world, is extremely complicated, whether it's practical, logistical, or financial. If we talk about being a woman, the dynamic is the same whether I’m shooting in London or in Palestine. It’s the same faction, it’s a very male-dominated industry regardless, but I come from an investment banking background, which is also a very male-dominated industry, so I’m accustomed to that. However, shooting in occupied territories like the West Bank posed complexities you wouldn’t find anywhere else in the world, like Israeli checkpoints and roadblocks... These obstacles contributed to creating tensions on set, especially when real-life events, like bombings in Gaza, coincide with our shooting. Everyone was on edge and anxious. One morning, on my way to work, I saw a family standing in front of their house freshly demolished by the Israeli army. Once again, that takes place in the film. So, I had to make sure we could finish the film, stay positive, and keep everyone safe. Which is a lot of stress and a lot of responsibility, both physically and artistically.

LC: You present vulnerability from another perspective by portraying the portrait of a Jewish father and his vulnerability in the face of his son’s disappearance. Why did you make this choice?

FN: For the character of Simon, the Jewish father, I was inspired by the kidnapping of the Israeli soldier, Gilad Shalit, in 2006, who was released five years later in exchange for over 1000 Palestinian prisoners, including hundreds of women and children. At the time, I remember thinking, “What an insane imbalance, one life for over a thousand others.” At the same time, I also remember contemplating and appreciating the universal love a parent has for their child and for whom they probably value the world. It's this dynamic that I appreciate, find powerful and important, and wanted to convey on screen. But most importantly, I wanted to draw parallels between Simon’s case, who has the power of the Israeli government behind him and a strong judicial system, with that of the teacher, Bassem Al-Saleh, who also lost his son and for whom legal recourse is extremely limited, as is the case for most Palestinians who have no recourse to justice. No matter how big the crime, no matter how massive the loss.

_________________________________

“I remember contemplating and appreciating

the universal love a parent has for their child a

nd for whom they probably value the world."

_________________________________

LC: What message did you want to convey through this film?

FN: I have no particular message other than to take the audience on an emotional journey in the hope of arousing interest and inviting them to question the lives and experiences of the characters, as well as the choices they made. And wonder, “What if I had been in this situation, what would have been my choices? What would I have done out of love for my child? If I lost him, what would I be willing to do to get him back?” Also, I believe I believe the film has the capacity to lend a context, generally absent from discourses, and which is nevertheless so important. Especially considering the last seven months of massacre that we have witnessed in Gaza.

LC: As a mother, how do you explain the current situation to your children?

FN: My children are teenagers now, but I’ve explained it to them over the years and in different ways. I'm not too heavy about it. I’ve taken them to occupied Palestine. So they will start to bear witness with their own eyes. I didn’t need to talk too much, if you will. They watched The Teacher twice. I guess, in a way, I explained to them what’s happening through my art. How else could I do it?

___________________

"Art speaks to the heart, not the mind."

___________________

_______________________

“I will always retain hope.

If I lose my hope, I will go insane.”

_______________________

LC: Do you still have hope?

FN: I am always hopeful, even as we are currently witnessing a plausible genocide and the absolute pain and suffering and loss and destruction taking place in Gaza, I will always retain hope. I don't really have a choice to be honest. If I I lose my hope, I will go insane.

A masterpiece to discover on streaming platforms from June onwards.

Thank you, Farah.

.jpg)