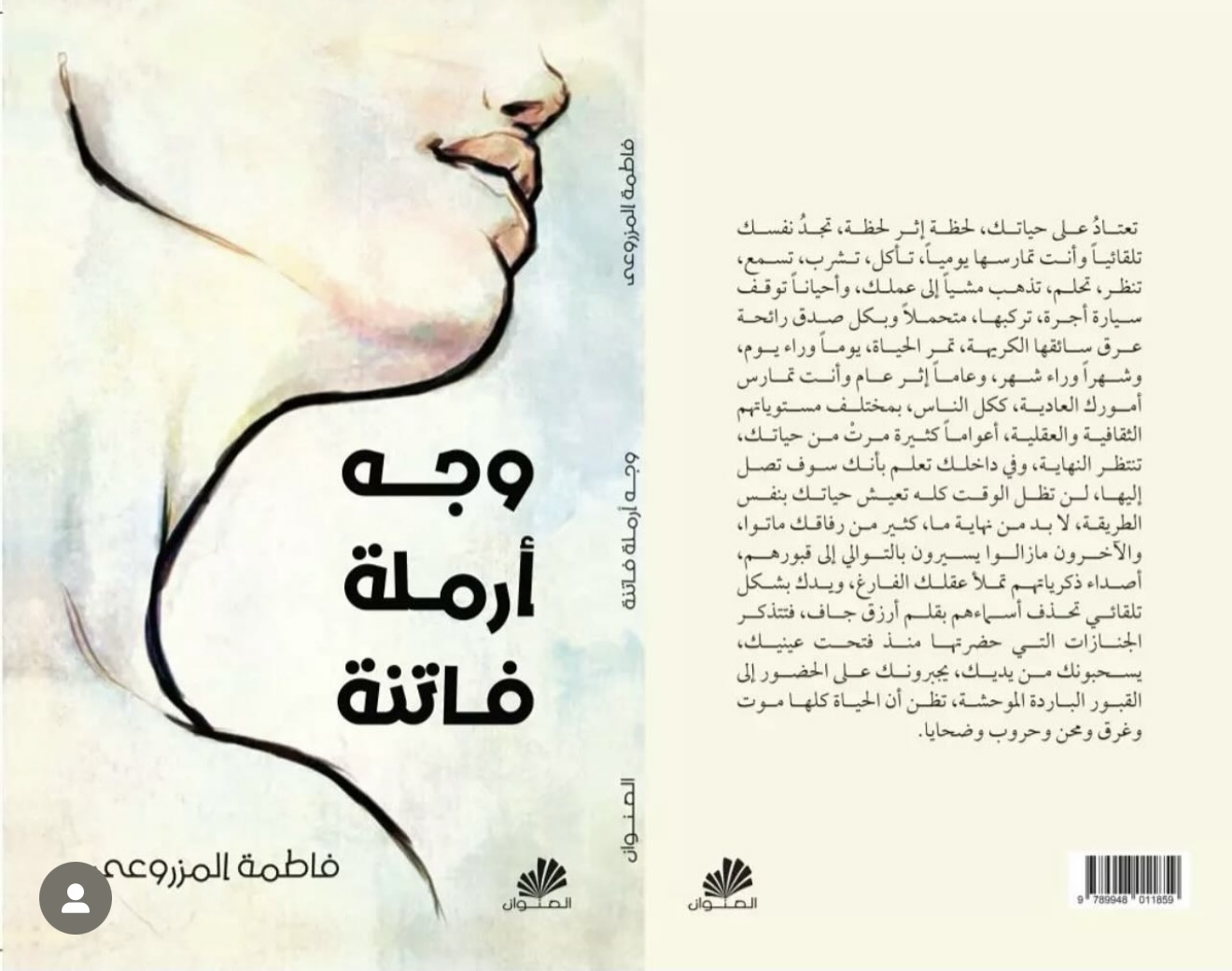

Qué rico es ser latino: How Bad Bunny Made the Super Bowl Speak Spanish

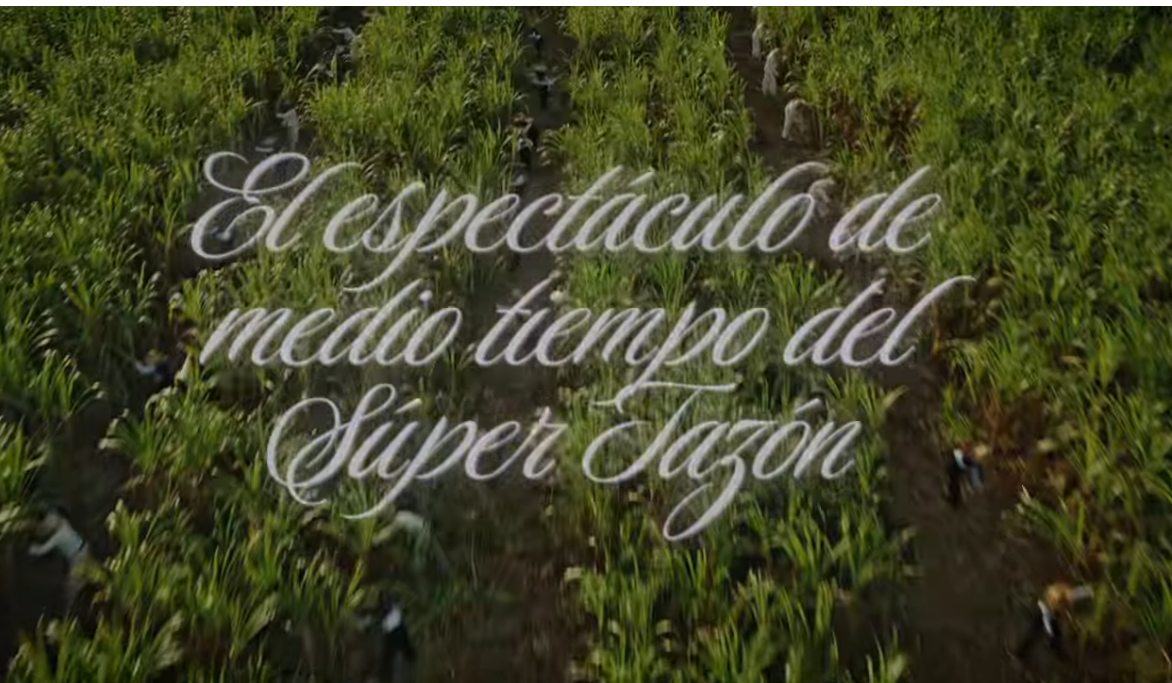

With the phrase “Qué rico es ser latino,” the Super Bowl halftime show began this February, during one of the most-watched broadcasts in the world. Without translations or explanations, those were the first words spoken on that stage. Immediately after, the official introduction of the show, also entirely in Spanish, named the artist by his full birth name: “Benito Antonio Martínez Ocasio presenta el espectáculo de medio tiempo del Super Tazón.” Even the name of the event appeared in Spanish. Spanish was not an accent or a gesture, but the language leading the spectacle.

Martínez Ocasio, known worldwide as Bad Bunny, is one of the most influential Latin artists of the past decade. Born in Puerto Rico, his career has redefined the boundaries of pop and global urban music, taking Spanish-language songs to the top of international charts without changing languages or diluting his cultural identity. His appearance at the Super Bowl, a space historically dominated by English and Anglo-American narratives, marked a symbolic turning point.

As a Latina, that opening felt instantly familiar. This was not a show designed to be explained, but to be lived. And yet, for audiences unfamiliar with Latin cultural codes, many of its images and gestures may have gone unnoticed. Not because they were obscure, but because they are rarely allowed to occupy the center of the global stage.

This text does not aim to translate Latin culture. It seeks to accompany a halftime show that functioned as a direct affirmation of identity: a love letter to Latin America that did not ask for approval, only recognition.

A Culture That Doesn’t Explain Itself: It Lives

The performance unfolded as a succession of scenes deeply recognizable to anyone who grew up in a Latin environment.

On stage, the wedding appeared loud, crowded, overflowing with people: music blasting, people dancing without perfect choreography, extended family filling every available space, a celebration that spills beyond protocol. In many Latin cultures, a wedding is not just the union of two people, but a collective event that belongs to the family, the neighborhood, and the community. Everyone takes part. Everyone is invited.

Within that same logic came one of the show’s quietest and most powerful images: a child asleep between two chairs. A small moment, easy to overlook, yet deeply charged with meaning. In Latin memory, the child who falls asleep in the middle of a party is a familiar figure. The celebration continues. No one leaves early. No one is left out.

Work as a Cultural Language

Another clear axis of the halftime show was the representation of everyday Latino labor: nail techs, piragua stands (Puerto Rico), raspaditos (Venezuela), coconut water sellers, and, most notably, a taco stand. Occupations that rarely occupy the center of global spectacles, yet sustain the daily lives of millions across Latin America and the diaspora.

The appearance of Villa’s Tacos, led by Víctor Villa, a Mexican American taquero and son of migrants, was not decorative but a political and cultural statement. A street-based business built on inherited recipes and constant labor was placed on the Super Bowl stage, elevating a food worker to the same symbolic level as global entertainment stars.

These scenes were not presented as folklore, but as living reality. In the United States, the Latino population represents nearly one fifth of the workforce, playing a crucial role in services, commerce, caregiving, construction, and agriculture. By bringing these occupations onto the Super Bowl stage, Bad Bunny turned the everyday into a symbol and made the historically invisible visible.

Hispanic and Latino Fashion

Bad Bunny’s wardrobe functioned as an organic extension of the halftime show’s narrative. The artist appeared in a monochromatic outfit by Zara, centered around a jersey bearing the surname “Ocasio” and the number 64 on the back, a reference to his ¨tio Cutito¨ year of birth.

By choosing a mass-market and widely recognizable brand, Bad Bunny broke with the usual expectation of luxury associated with this kind of stage. Instead of presenting fashion as something inaccessible, he built a message rooted in identification: a familiar garment, part of the everyday experience of many Latinos. Fashion appeared not as an unattainable aspiration, but as a shared language.

For many Latinos, Zara has been—and continues to be—a gateway to fashion. It occupies an intermediate aspirational space that shaped a generation who learned to build personal style by blending global references with their own identities. In that sense, the wardrobe spoke less to exclusivity and more to collective memory.

Lady Gaga’s wardrobe offered a complementary reading within the same cultural narrative. She appeared in a custom-made dress designed by Raúl López, founder of LUAR, a brand of Dominican origin. Conceived in the colors of the Puerto Rican flag and finished with a brooch inspired by the maga flower, the island’s national symbol, the design translated Latino identity into the language of contemporary high fashion.

A Genealogy of Latin Music: From the Margins to the Center

The halftime show traced a clear line through the evolution of contemporary Latin music. The appearance of Ricky Martin recalled the first major crossover of Latin pop into the global mainstream, when Spanish began to occupy central stages without fully disappearing.

That trajectory continued with reggaeton through brief musical fragments referencing foundational figures such as Celia Cruz, Daddy Yankee, Tego Calderón, and Don Omar, underscoring how the genre’s current prominence is the result of years of cultural persistence. The inclusion of Giancarlo Guerrero, leading a string ensemble during one of the transitions, expanded that lineage by momentarily bringing orchestral sound into the frame, linking popular and formal musical traditions often kept apart.

Within this context, Lady Gaga appeared as a gesture of cultural coexistence. Accompanied by Los Sobrinos, she performed Die With a Smile in a salsa arrangement before joining Baile inolvidable, aligning with the rhythm of the show without shifting its core narrative.

Bad Bunny emerged not as a rupture, but as continuity: part of a collective history that now places Latin music at the center of the global stage.

Toñita and the Diaspora as Living Memory

For those unfamiliar with the Puerto Rican diaspora in New York, Toñita may not be a recognizable name. María Antonia Cay is the founder and owner of the Caribbean Social Club, a cultural space that for decades has offered dominoes, merengue, food, and community to generations of Latino migrants in the city, not as a trend, but as a home away from home. Far more than a bar, the club has remained a symbol of cultural continuity and resistance in the face of forces such as gentrification that have reshaped New York.

Her appearance during the halftime show, after being mentioned in one of Bad Bunny’s songs, brought that living memory to one of the most-watched stages in the world, reminding audiences that Latino identity is sustained not only through performance, but through the spaces and people who preserve it every day, even by responding to urgent needs such as food insecurity within the community.

Toñita is culture, generosity and permanence.

Benito as a Reference of Latino Resilience

There is a gesture that runs through the entire halftime narrative and feels deeply recognizable within the Latino experience: the insistence on saying yo creí — “I believed.” Believing in oneself, in our contexts, is rarely a comfortable starting point. It is sustained by intuition, stubbornness, and faith more than by guarantees.

When Bad Bunny says, in Spanish, “If I’m here today, at Super Bowl LX, it’s because I never stopped believing in myself. And you should believe in yourself too,” he speaks from a shared experience shaped by generations who learned to move forward without a manual.

That message deepens with the appearance of the child who represents his younger self, to whom he symbolically hands the Grammy. The gesture is not a celebration of the award, but a return: recognition traveling back to its origin. That child is not only Benito, but a collective figure. In the Latino narrative, moving forward does not mean shedding one’s origins, but proving that arrival was always possible from there.

God Bless America: Redefining a Shared Continent

Toward the end of the show, Bad Bunny redefined one of the most repeated phrases in the U.S. imaginary: “God bless America.” By naming the countries of the continent and unfurling their flags, he expanded the meaning of America, returning it to its geographic and cultural scope.

That gesture was reinforced by an American football bearing the phrase “Together We Are America.” One of the most recognizable symbols of U.S. national identity was re-signified to communicate a broader idea of belonging.

In that sense, the joy that ran through the show was neither escapism nor excess. It was transmission. It did not need to be explained or translated to fulfill its purpose. Through music, dance, and shared laughter, something basic and profound was affirmed: there is nothing to correct in these rhythms, in this way of feeling. Shown as it is, celebration interrupted a deeply ingrained logic within the Latino experience in the United States: the idea that acceptance requires reduction.

The reaction was immediate. For some, the show was “too Latino” or “hard to understand.” For others, that was precisely its power. That the performance unfolded almost entirely in Spanish was neither an oversight nor a provocation, but an affirmation.