Bally Foundation Reveals Exhibition with Saudi-American Artist Sarah Brahim

In his Ethics (1677), Spinoza argued that the spirit cannot destroy itself with the body, and that by knowing this, “we know by experience that we are eternal.” (1) Three hundred years later, French philosopher Alain Badiou added the word “sometimes” to this proposal: “sometimes, we are eternal.”(2) With this adverb, he situated eternity in time. “Sometimes” suggests a sensation, a moment, and a new relationship between the finite and infinite, between universal truths and specific bodies. Eternity could then be defined as a form of infinity in a finite world: the possibility of being brought to a standstill within ourselves, in the inner experience of our own infinity.

In Sometimes we are eternal, Brahim sets out to retrace the past ten years of her life, looking back across the temporal distance that separates this project from an event that changed its course: the tragic loss of a loved one. By “making a stop in time that is also the construction of a new time”,(3) the artist explores the ins and outs of what she calls the “intrabody” and of the surrounding universe. Trained as a dancer, Brahim gives her artworks the appearance of a pas de deux, an intimate dialogue between the dancer and her alterities, in which the form of the exchange remains fluid: this “dialogue” is that of her interiority, between a body that transforms itself and another that transmits, one that abandons resistance for acceptance and another that embraces embodiment. Perhaps this is how the suture between the finite and the infinite operates: the artist allows us to observe, perceive, and understand her as she becomes the subject of different forms of this infinity, an immanent trace within human finitude.

But how can we be transformed by our own gestures, in our bodies, by invisible forces, without fixing the contours? Brahim is interested in transformation, in the localization and dislocation of the self through the body, seeking “a constant rebalancing of the relationship between vertigo and precision,”(4) which could be one of the central articulations of her work, in that it does not imply an absolute but places events on a spectrum of entering and leaving a state of consciousness.

The artist is certainly inspired by dancers and thinkers who, in the 1960s and ‘70s, thought of dance as a heightened experience of life, a search for symbiosis of body, consciousness, and environment. Anna Halprin, considered as one of the pioneers of modern dance, developed a practice that included “tasks” to accomplish, simple actions repeated over and over to focus on the body’s perception and sensitivity. As a result, her pieces moved out of the theater, into the streets, into nature, where she also explored, thanks to the minimalist architectures designed by her husband Lawrence, the use of these dance protocols to help people cope with emotional stress. Around the same time, the philosopher and movement practitioner Thomas Hanna published Bodies in Revolt (1970), in which he defines “soma” as the entire living human process, the body perceived from within, concentrating both mental and physiological events into a single process—essentially, the way in which one’s history, thoughts, images, emotions, and sensations come together and are incorporated and manifested in the experiential body. These precedents suggest a possible interpretation of the “tasks” that Brahim explores in her videos and photos: walking, breathing, rising, falling... Simple choreographic texts, to which are added intermediary elements such as light, water, and sound. Body as memory, body as medium, body as reincarnation: our presence in the world, the trace we leave on it transforms the protocol of walking into the score for a landscape. In this way, the ten works in Sometimes we are eternal are each small nuances of a larger theme, in which each work almost speaks of itself. Suspended bodies, breaths, imprints, rhythms, and rituals mingle and follow one another, in installations that extend these back-and-forth movements from the physical body to the “intrabody,” the imperceptible, the spiritual, the distant. The architecture fades away, leaving an expanse as abstract as a dance studio, mental, resilient and luminous, offering the spectator a sense of spatial uncertainty. By immersing ourselves in this sort of landscape, we come to see it as a resource, without focusing on its material dimension: to contemplate it, to anchor ourselves in it, in order to acknowledge it as a space of experience and dialogue, where an intimate collaboration can take place.

The exhibition is closely connected to the place for which it was conceived, the Villa Heleneum, which was built by a dancer, and in which transparency, the presence of water and uncontaminated landscape, surrounds the works, conceived as a collection of fragments, abandoned memories, portions of objects and gestures, readings and sounds. In her creative process, the artist also often refers to the work of Italian architect Aldo Rossi, for whom the question of the fragment in architecture was crucial, composing her creations with inserts or relics of time, symbols of a certain continuity of form, morsels of pre-existence capable of connecting us with what has gone before.

First Floor: Rhythm and Matter

.jpg)

The artist’s reflection on the different ways of being connected is apparent from the very first piece, The second sound of echo: in the intimacy of a very small room, we witness the transfer of physical impulses between two bodies, the artist and her father. Two stones, rubbing against each other, set the tempo, aiming to produce a spark, while one body sways, seeking unison. The rhythm seems to be that of heartbeats, sometimes in synch, sometimes irregular, evoking how one body existed before the other, how both existed simultaneously, and how one will inexorably disappear, while the other continues on. This suggestion of fusion is also present in the Untitled images in the next room, where two hands clasped on the horizon and a body on a beach seek to integrate the landscape.

.jpg)

The next work, She said, it’s always two bodies, focuses on the body and our experience of movement from a scientific and spiritual point of view. The artist creates an installation in which she achieves a kind of synthesis between form and function, with the materialization of her body at work, feeling its way through the material, abandoning itself to it. The soundtrack—cracks, whispers—helps us to penetrate the interior of this earth. On the one hand, this breakthrough into the flesh of the world; on the other, its trace.

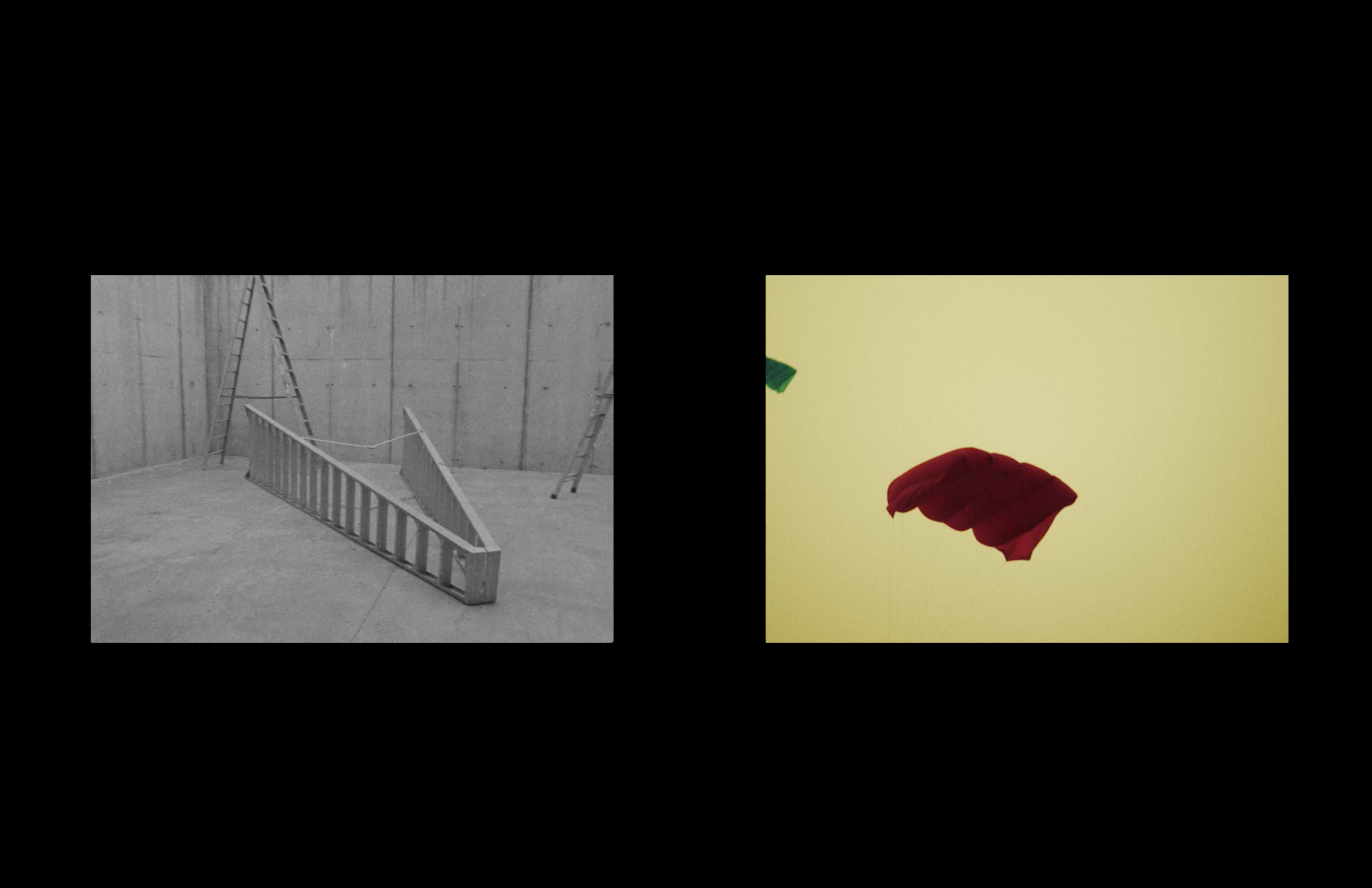

While almost all the works in the exhibition deal with the question of time, the multi-screen video installation Duet with time uses an enigmatic ladder placed in the center of a courtyard, on which two performers rise from the ground to attempt an ascent. In this piece, the ladder becomes the spine, leading to the initiation and the fragmentation of steps, introducing the ability of certain forms to evoke ritual, giving free rein to the body’s intelligence and the mechanics of repetition. This repetitive, very slow, almost infinite movement is also the subject of I like never, I also like ever, a video installation that places the viewer at the center of these same two levitating bodies. Clarice Lispector, in her book of meditations, Agua viva (1973), writes “As if in levitation. My mind is empty of so much happiness. The intimate freedom I feel can only be compared to an aimless walk in the fields. [...] I have ceased to be tormented. Such is grace.” (5) In this way, I like never, I also like ever liberates bodies, leaving them in a state of permanent suspension and in the momentum of a movement that fragments into thousands of images that take time to see and feel. Starting with a classic dance figure, the plié-sauté, Brahim removes the beginning and end points, as if repelling gravity, to sustain this moment of levitation.

.jpg)

Second floor: Memory and disappearance

A sound piece follows, focusing on the memory of childhood: the period of life during which, according to Pauline Oliveros, a pioneer of electronic music, our relationship with sounds as the language of emotions is formed, as is our capacity for deep listening.(6) For the piece No wrong sounds, Brahim returned to a practice from her childhood, tap-dancing, and worked with a group of tap-dancing students under the age of 10. She gave them simple tasks, such as standing in a circle and performing the rhythm of their own heart or the sound of a river. Of course, everyone dances to their own inner sound, as they also seek to tune in to each other, creating a form of harmony. All these movements also left a radial trace on the floor, like an imprint on the exhibition landscape.

This journey into buried memory continues with a light installation, The Lightroom. Its hypnotic pulsation of light takes the viewer back to a very personal form of trance, but also to the beam of lighthouses projected into distant waters. And it’s to the ocean’s edge that we continue with the video installation Adagio. On one side we see the artist walking extremely slowly along the ocean’s edge, with a camera mounted on her diaphragm, while on the other we see the sea filmed by this camera, breathing at the artist’s pace. Her body is transformed into an instrument of synchronization with the shutter, and breathing gives rhythm to the elements. The artist becomes a vector of vulnerability and connection, taking almost literally the words of Astrida Neimanis, a theorist working at the intersection of feminism and environmentalism: “For us humans, the flow and flush of waters sustain our own bodies, but also connect them to other bodies, to other worlds beyond our human selves. Indeed, bodies of water undo the idea that bodies are necessarily or only human.” (7)

.jpg)

We then move through a series of photographs that seem to be the research collection assembled to make these works, isolating precise moments when the body is sometimes evanescent, evaporating in the landscape, sometimes caught up in the material, in total fusion with the rocks or the earth. The last work in the exhibition, the video installation He said, we must forget, presents two films running in parallel. Using images collected over the course of an entire year, two films intersect and oppose each other, one undoing what the other brings forward, with a technique based on hand-painting. Through fragments of images, of sensations, Brahim tries to understand how we involuntarily forget certain things to move ahead, how our memories become blocked, block our access to memories: how do we go back? How do we separate memory and imagination? “To be born is to be nothing other than a reconfiguration, a metamorphosis, of something other. To be born . . . means having to construct, to build one’s own body from the Earth, from all the matter available on this planet of which we are both the modification and the expression, both an articulation and an unfolding. To be born is to be made of the same material from which all things before us were made.” (8)

1. Ethics, Spinoza, proposition 23, 5th part, Princeton University Press

2. Sometimes we are eternal, Alain Badiou, Nick Nesbitt, Kenneth Reinhard, Jana Ndiaye Berankova, Directed by Jana Ndiaye Berankova et Norma Hussey, Suture Press

3. Ibidem

4. La danse comme métaphore de la pensée, in Petit Manuel d'inesthétique, Alain Badiou, Seuil

5. Agua viva, Clarice Lispector, Penguin books

6. Sonic Meditations, Pauline Oliveros, Ingramspark

7. Bodies of water, Astrida Neimanis, Bloomsbury Publishing

8. Metamorphoses, Emanuele Coccia, Polity Press

.jpg)

.jpg)